The Evolution and Brilliance of Ethiopian Crosses

The Ethiopian Orthodox Church has retained a strong role in the lives, culture, and religion of its members from the time Coptic Christians arrived from Egypt in the 4th century A.D. to the current day. Ethiopia was the second country after Armenia to accept Christianity as its official religion, and Ethiopians remain among the world’s staunchest adherents to the Christian faith. Although it initially fully embraced Christianity, the Ethiopian Orthodox Church forged its own cultural and religious path and maintained its independence from European influence. Until the early 15th century, it remained isolated from the outside world. In the 16-17th century there was limited contact, but that was followed again by two centuries of isolation. Thus, for most of its 1600 year existence, Ethiopia flourished by following its own religious course independent from outside influences. This enabled the Church to retain much of its early simplicity, purity, symbolism, and the practices that were derived from earlier Christian cultures. (Heaphy)

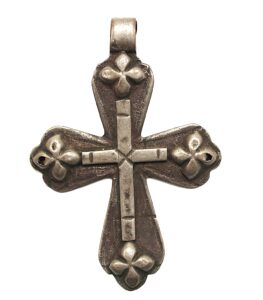

The cross is one of the oldest and most predominant symbols of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, and no other region has produced the quantity, quality, and diversity of designs as the Ethiopian highlands in Ethiopia and modern Eritrea. Ethiopian artisans have historically produced beautiful crosses with ornate and unique designs that reflect local differences in styles and interpretations as well as their highly skilled talents. Their crosses reflect spiritual piety and are a “source of blessing, power and protection under God… [and Christ who is viewed as the]…“redeemer, protector and benefactor of humanity.” (Abbink). Their uniqueness stems from blending of influences of many ancient civilizations: Coptic, Celtic, Egyptian, Byzantine, Greek, and Latin.

Crosses are called meskel in Ge’ez, the liturgical language of the Ethiopian church, and they are ubiquitous in Ethiopian and Eritrean cultures. They are everywhere; behind altars, carried in processions and by individual priests for blessings, used inside homes, and worn by all as small pendants. There are four types of crosses: staff, processional, hand-held, and pendant. (Balicka-Witakowska) Staff crosses are a long staff topped with medium size crosses forged from iron and are used by both wandering monks and important monastic figures. Processional crosses are huge and elaborate, mounted on shafts, and carried in churches ceremonies. Hand-held crosses are about 12 to 24 inches long and used only by clerics and monks, and other crosses from about 4 to10 inches are held by priests and used for blessings. Pendants, also called neck or pectoral crosses, are the most common, numerous, unique, and are fabricated by local metalsmiths in many villages. Since metal was initially rare in Ethiopia crosses were initially made from wood, bone, and leather. In the late 18th century when Arab merchants brought Austrian Maria Theresa silver coins called Thalers to Africa, silver became the material of choice for Ethiopian crosses. Thalers rapidly became the national Ethiopian currency and were the unofficial monetary exchange in some parts of Africa, Asia, and the Arab world for the next 150 years due to its purity and uniform weight. Originally struck in 1740 to 1780, they were in such great demand, restrikes occurred through the 19th century. Thalers were melted into sheets of silver and cut to fabricate larger crosses, and in the late 19th and early 20th century were melted for use in lost wax molds for pendant crosses. Contemporary pendants are manufactured, cast, or cut in a single piece from a variety of metals, many of which still have silver content. (Balicka-Witakowska)

Ethiopian crosses are referred to by several names including Coptic or Abyssinian crosses and by the name of the Ethiopian regions or towns where they were created. The three main styles are Axum, Gondar or Lalibala, and the majority of neck pendants are made in the Axum style, created in the Tigrai region of Ethiopia and in Eritrea. (Heaphy) Although European crosses are based on the Latin cross, they are primarily based on Coptic prototypes.

Coptic Style Appliques, Punctations (E328)

Ethiopian crosses are based on the Latin cross, they are primarily based on Coptic prototypes.(1 ) Circles were often included in the design of old Coptic crosses, and they sometimes included the Egyptian circle called the ankh surmounted on a Latin cross. (Beyer). Although the ancient Egyptians believed the ankh represented the sun god and eternal life granted by the gods, the Copts believed the circle symbolized Christ’s halo, divinity, and God’s everlasting and eternal love brought to man through the Sacrifice of His Son on the cross and resurrection.

An Image from Wikipedia of a Prototype Coptic Cross with an Egyptian Circle of the Ankh Surmounted on a Latin Cross.

Modern Coptic crosses created since the 19th century are often made with two thick arms of equal length dividing the cross at right angles, and many of these have three points on each of the four ends and are called a cross fleury symbolizing the Trinity. When combined, they have 12 points that symbolize the 12 Apostles who spread the Gospel. Although design elements are added to crosses using well-recognized symbolism and iconography, the wide variations that characterize these crosses reflect style and interpretational differences from the areas and regions where they were created and also the unique sensibilities and talents of highly skilled artisans. An even greater variance of contemporary pieces also results from artisans mixing designs, shapes, and patterns emanating from several regions in a single cross.

Pendant Crosses

Ethiopians have worn pendant crosses since the first millennium of Christianity when they were introduced from the Roman and Byzantine civilizations. (Southworld) They are spiritual symbols demonstrating their followers’ devotion to Christ and reflect the direct relationship of Orthodox Christian Ethiopians as descendants of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. Made in a variety of sizes, designs, styles, and ornamentation, pendant crosses are worn by all Ethiopian Christians and are especially revered by women. (Balicka-Witakowska) Worn around the neck hanging at the chest over or underneath their clothing they are often suspended on a blue cotton thread or tri-colored cord called a mateb. The mateb is one of the earliest Ethiopian symbols of Christian faith made of white, red and black woven strands symbolizing the Trinity. (Southworld). They are decorative personal ornaments with a religious significance that display variety and creativity in both form and design while reflecting the regional styles of the artisans who created them. They are presented to newborns at baptism and become cherished possessions passed down through generations. Many are decorated on both sides with etched, soldered, and punctate designs and usually have a small soldered top suspension loop for the cord to pass through. Since they are worn constantly, they often require repair by local metal smiths.

Pendant crosses have traditionally been made using the “lost wax” casting process (cire perdue) in which metal is poured into a wax mold covered in clay, and dried. The mold is broken creating a one of a kind work of art to which decorative etching, stamped designs, and additions might be later attached. Early 19th and 20th century crosses were made using melted Austrian Thalers containing a regulated content mixture of.833 silver and .166 copper. With many Thaler restrikes the creation of crosses increased. Since they were created throughout Ethiopia and Eritrea over a long time period and sometimes contained a a variety of mixed metals it is very difficult to verify either their silver content or precise origin.

These pendants blend spiritual, community, and personal beliefs and are a a form of interacting between human and divine spheres. Since the 15th century, their intricate designs and symbols have been metaphors for the religious beliefs, ideology, and practices of the Ethiopian Church recognized by devotees in all levels of society. Most crosses made through the early 20th century conformed to church doctrine, and some scholars believe were made under the auspices of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church made by Church trained artisans.

Interior Cross, Tri-Part Arms (E335)

Well-understood symbols and forms were base of the crosses which were embellished with unique creative details. Highly ornate and symbolic designs include trefoils with overlapping rings, detailed openwork, intricate geometric patterns, projections and flared decorated arms. The most predominant artistic features of all types of Ethiopian crosses are the intricate filigree latticework and patterns of knotted and interwoven threads that signify core beliefs of the Ethiopian Church.

Maria Evangelatou has brilliantly explored this in her paper on the symbolic language of Ethiopian Crosses where she asserts this threads design motif, which required skilled and labor intensive artisanship, reflects practical, artistic, spiritual, and protective concerns. The voids in the patterns require less metal, making the crosses more economic to make and lighter to wear. The delicate matrixes elevate the artistic beauty and unique radiance of each piece and create interplays between light and shadow, contrasting material presence and absence, and juxtaposing materiality and immateriality. The thread-like elements are a never-ending knot without a beginning or end symbolizing eternity and everlasting life as well as unity and order and the “…union of humanity and divinity in Christ that makes possible the salvation of the world; and the union of matter and spirit in all human beings and their experiences, as well as in their hopes for both physical and spiritual salvation, the well-being of body and soul.” (Evangelatou) As explained below, the knotted patterns are also apotropaic symbols that protect and heal humankind and ward off evil. In later forms, the latticework is represented by etched crosshatching on the surface of the cross.

Crosses are enhanced by motifs that enrich their symbolic significance and refer to the history of the world and human salvation as seen through the eyes of Ethiopian orthodoxy. The cross itself visually symbolizes piety and protection and is “…identified with the life-saving, protective and blessing force” (Abbik).

Axum Style Incised Meander (E306)

Stylized images of birds with the cross transforms it into a symbolic tree, and it becomes the Tree of Knowledge and the Tree of Life that provides wood for the True Cross and mirrors the circle of life marking the beginning of mankind and humanity’s return to paradise. Birds may also be symbols for the Holy Ghost.

Circles, Crosses, Birds (E303)

Fleury Applique Pattern Small Dots (E339)

Crucifix Style with Appliques (E334)

Orthodox Ethiopians wear crosses not only for spiritual reasons but also to promote the healing of the body and spirit and provide protection from evil. Some crosses are commissioned as apotropaic objects, talismans, or amulets infused with special magic powers that can repel evil forces, avert harm, deflect misfortune, and prevent curses and the “evil eye.” (Balicka-Witakowska). The cross itself, as well as certain design features in the shape of a cross, is also said to have the power to ward off evil. Some symbols appearing on Ethiopian churches and crosses are considered spiritual protective markers with special magical powers that bring blessings and protection to devotees. A major apotropaic symbol called the ‘labyrinthine meander’ is commonly used in the form of lattice knotted patterns of endless lines that overlap and weave within each other and are seen as thwarting malevolent beings from entering or reaching believers, as evil spirits follow the endless lines and become entrapped in them for eternity. Likewise, incised and scratched criss-cross or mesh patterns also conquer demons by trapping them inside the net they create. (Fairey) Circular shapes, designs, and radiating shapes within circles are “protective eye” apotropaic symbols with magical properties that bring personal blessings to the wearer, deflect misfortune, repel evil forces, and harm and avert the “evil eye.”

Central Maltese Cross, Birds, Protective Eyes (305)

Meander, Crosses, Circles, Protective Eyes (E325)

Radiating Beams Inside Circle ( E308)

Another motif of Ethiopian Crosses is the Star of David. Tradition states that the first Jewish people came to Ethiopia during the extended drought and famine in Canaan at the time of Abraham (1812-1637 BE). A Jewish Ethiopian empire called the House of Soloman (Solomonic Dynasty) made up of descendants from the biblical King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba ruled there from the 10th century. Their tradition states that the queen gave birth to Menelik I after visiting Solomon in Jerusalem as described in the Old Testament. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church was founded in the 4th century CE, when both religions were practiced there, and this accounts not only for the Jewish star (the Star of David) occurring in Ethiopia but also for many of them having a cross in their design.

Star of David, Cross Inside, Circle (E341)

For the past few decades, Ethiopian Crosses have been considered trendy decorative items, acquired as a fashion statement. While these pendant crosses are attractive accessories and may be viewed as fashion statements, they should be understood and appreciated as unique and revered personal and spiritual items. They are much more than they appear to be at first glance, and a broader understanding of their meaning and history will result in a greater appreciation of their uniqueness and cultural and spiritual importance.

Sources:

- G. J. Abbink, “The cross in Ethiopian Christianity: ecclesial symbolism and religious experience,” in E. K. Bongmba (Ed.), Routledge Companion to Christianity in Africa, London, Routledge, 2016.

- Catherine Beyer, “What Is a Coptic Cross?” Learn Religions, May 8, 2019, https://www.learnreligions.com/coptic-crosses-96012

- John Bradfield, Ethiopia: King Solomon, “The Queen of Sheba, and the Back Jews-Part 1,” February 18, 2012 , This ’N That, https://johnlbradfield.com/religion/ethiopia-king-solomon-the-queen-of-sheba-and-the-black-jews/

- Ethiopia Tropical Tours, “Bahir Dar, Gate to Lake Tana,” https://ethiopiatropicaltours.com/sight/bahir-dar-and-lake-tana-ethiopia/

- “Ethiopian Cross,” https://www.seiyaku.com/customs/crosses/ethiopian.html

- Maria Evangelatou, “The Symbolic Language of Ethiopian Crosses: Visualizing History, identify and Salvation through Form and Ritual,” January 6, 2013, Hawaii University International Conferences Arts, Humanities & Social Sciences, www.huichawaii.org/assets/evangelatou_maria_ahs_2013.pdf

- Charles E.S. Fairey and Vincent Reed, “Apotropaic Ethiopia: Early examples of Spiritual Protection from Christian Africa,” March 6, 2019, https://apotropaicethiopia.wordpress.com/2019/03/06/knotwork-crosses-and-the-labyrinthine-meander/

- Doug Gray, “Christian Symbology,” https://www.christiansymbols.net/crosses.html

- Linda Heaphy, The Ethiopian Cross, March 20, 2017, https://kashgar.com.au/blogs/ritual-objects/the-ethiopian-cross

- Paul Raffaele, “Keepers of the Lost Ark?” in Smithsonian Magazine, 2007 https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/keepers-of-the-lost-ark-179998820/

- Southworld News and views, “The variety of Ethiopian crosses,” September 2014 http://indigenousjesus.blogspot.com/2014/11/southworld-article-variety-of-ethiopian.html

- Wikipedia, Coptic cross, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coptic_cross Ewa Balicka-Witakowska, “Crosses of Ethiopia,” Institute of Linguistics and Philology, Uppsala University, Sweden, https://www.barcelona.cat/museu-etnologic-culturesmon/montcada/en/collection/discover-the-collections/discover-more/crosses-of-ethiopia