The Allure of Shiwan Pottery

Traditional, decorative, and utilitarian Chinese ceramic pieces produced at the Shiwan kilns in Foshan City located in the southeastern Chinese Province Guangdong that borders Hong Kong and Macau are well recognized and respected around the world for their fine modeling, vivid expression, and colorful glazes. Kilns in this area date back more than 4,000 years and reached their height of production during the late Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) periods. They are also famous for producing household and utilitarian items as well as finely modeled figures with vivid expressions and vibrant glazes. The most well-known and serviceable pieces are the cooking vessels and teapots that impart an earthy flavor to the food prepared with them. In the early and mid-1800’s, Shiwan pottery became a hallmark for the preparation of Cantonese cuisine sought by food aficionados and collectors from around the world, including the British, Americans, and Portuguese. Their originally rather inexpensive glazed stoneware was imported by American Chinese in the 19th and early 20th centuries and used for home cooking in Chinese homes and communities across the country as well as in restaurants. (CINARC)

One of the Earlier Artistic Forms of Recycling

In contrast to China’s imperial and large independent kiln sites, potters from Shiwan in Foshan were modest craftsmen renowned for transforming common materials into beautiful and colorful creations. As most of these potters were poor, they creatively reused some waste materials in their production, including local coarse sand and inexpensive clay while producing basic daily utensils and pottery. This was perhaps one of the earliest and artistic forms of recycling. For centuries Shiwan potters used long “dragon kilns” to fire their creations which often produced uneven heating conditions with both undesirable and desirable consequences. While some glazes were simply ruined, others produced unique artistic effects, combinations, and a wide range of distinctive and artistically intriguing colors and tiny “sesame dot” markings. Their pottery pieces are admired for their brilliant flambé or flame-like quality of dripped glazes in vibrant black, brown, red, and, most characteristic, a fine and universally coveted apple-green. As noted by Scollard (p. 51) “Irregularities in the glazing due to materials used and inconsistencies of kiln temperature are characteristic of Shiwan ware and add to its unique charm.”

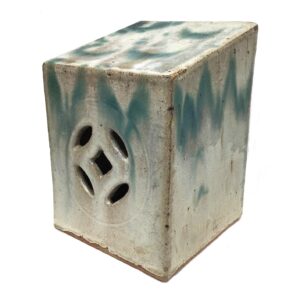

Charm in Everyday Objects, the Ubiquitous Chopstick Holder

Known as the “Pottery Capital” for centuries, Shiwan potters produced many pottery objects for household use for a variety of every day needs – pots, cups, pitchers, plates, vessels, storage containers, wall vases, chopstick holders, candlesticks, oil lamps, other utilitarian pieces as well as opium pillows. A similar example of this pair of opium pillows is included in the catalog of the 1994 exhibit organized by the Chinese Culture Center of San Francisco by Scollard (p. 51)

Potters “bread and butter” pottery pieces include teapots and chopstick holders. Chopsticks are very significant accessories in China and often included in a bride’s dowry, as the word for chopstick (kuaizi) is also a homophonic pun meaning “speedy arrival on sons” (kuaizi). (Bartholomew, p. 66) So, Chinese traditionally fasten chopsticks above the door of the bride’s room as a wish for a speedy pregnancy. (Welch, p. 10) As the primary goal of a Chinese wife was to produce sons to carry on the family name, one can more fully appreciate the importance of the pun on the chopstick holder. Only sons were permitted to participate in the rituals honoring one’s family, and daughters left their family with a dowry to live with her husband’s family. This resulted in a net loss of family wealth, and females had only one way to increase their family’s fortunes: give birth to sons.

As in all Chinese folk art, utilitarian items are fraught with symbolism. Chopstick containers traditionally display four characters either across the top or on the sides of “baize qiansun,” which is a wish for a hundred sons and a thousand grandsons. An image of a bat (fu), one of the most widely used and popular symbols in Chinese art, hovers in the center sometimes holding a coin in its mouth that symbolizes blessings, as the word bat is homophone having a similar tone in Chinese as the words for blessings (fu) and riches (fu). Chinese coins are a symbol of wealth, and ancient coins are also said to ward off evil. The shape of a Chinese coin, which is a central square within a circle, reflects the old Chinese idea that the earth is square and heaven is round (Bartholomew, p.136). The two images together of the bat symbolizing blessings, and coin (qian) which is homophonous with the word “before” (qian), along with the coin’s square opening which is called an “eye” (yan), together are a wish for blessings “in front of your eyes.”

Recognition as a Fine and Unique Pottery Tradition

Overshadowed by the fine porcelains manufactured at the imperial kilns throughout China, Shiwan ceramic wares were historically under-appreciated. The Shiwan pottery industry was mainly seen as creating mass-produced household utensils and pottery for common folks. Before the 1950’s, even the museums in Guangzhou did not acknowledge the importance of these wares. In the past several decades, however, appreciation for Shiwan wares and its unique glazes have been transformed, appreciated, and highly prized as a distinctive, respected, and now a very highly collected art form. In 1994 the Chinese Culture Center of San Francisco organized the exhibit and accompanying book Shiwan Ceramics: Beauty, Color and Passion (Fredrikke S. Scollard and former Asian Art Museum of San Francisco curator Terese Tse Bartholomew). The cultural center of San Francisco and the Pacific Heritage museum also co-presented the exhibit Shiwan Ceramic-Rustic Splendors: Kiln Treasures from August 26, 2005-March 23, 2006 which stated “Although it has never received imperial patronage, Shiwan wares have earned recognition beyond their remote provincial place of origin…This tradition continues to the present day as evidenced by the high demand for utilitarian Shiwan ware.” (Leung)

Published Sources

Terese Tse Bartholomew, Hidden Meanings in Chinese Art, San Francisco, Asian Art Museum, 2006.

Patricia Bjaaland Welch, Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery, Tuttle Publishing, Singapore, 2008.

Fredrikke S. Scollard and Terese Tse Bartholomew, Shiwan Ceramics: Beauty, Color and Passion, San Francisco, The Chinese Culture Foundation of San Francisco, 1994.

Online Sources

www.cinarc.org, Chinese in Northwest American Research Committee (CINARC), “The Products of the Foshan Potters’ Guilds,” January 14, 2015.

www.cccsf.us, Jenny Leung, “Rustic Splendors: Kiln Treasures from Shiwan,” August 26, 2005.