Indonesian Dance Masks (Topeng): Spiritually Connecting the Community

People are always impressed by the variety and aesthetic appeal of Indonesian masks when they first encounter them, but they are usually unaware of their meaning, history, and cultural importance. When masks were first used in Indonesia is debated, but they probably were rooted in its ancient animistic past. Animists believe that spirits and gods are present in all things, and most scholars believe the first masks used world wide in ceremonies and rituals by “primitive” peoples were intimately tied to their animistic beliefs combined with ancestor worship where dancers were considered as communicators to and interpreters of the gods, ancestors, and spirits. Celebrations where masks are worn on the face, used in ritual dances, hung on walls in houses, placed in burial sites to honor departed ancestors, or even made into motifs on clothing to link villagers to their ancestors, gods, or spirits are still used by indigenous tribal groups to aid communication with them, attract, please, and entertain them and either ask them for blessings and a reciprocal connection or satisfy or placate malevolent ones so they will keep their distance, be scared away and not bring disease or negative energy to the village. An example of this is the Dayak Hudoq celebration in Kalimantan where ancestors, gods and their many spirits are honored by celebrants where masks (also called Hudoq) are used as a welcome and entreaty, and also pleasing amusements are provided to bring favor and protection or to gratify evil forces to keep them at bay. In Dyak tradition festivities are often connected to agriculture, especially planting and harvesting, and are seen as a way to protect crops from pests (also called hudoq) and prevent floods, famine, and drought as well as provide entertainment not only for gods, spirits, and ancestors but also for all living attendees.

Historical Precedents

When traders, sailors, scholars, and priests in the 1st century CE, brought Hinduism and Buddhism to Java, the existing folk religion was steeped in animism. Influenced by Hindu and Buddhist ideas, it evolved into a unique Hindu kingdom by the 5th century. Stories from India from the Sanskrit Hindu epic poems the Ramayana and Mahabharata soon began to be performed as dramas and dances. Rama is a major Hindu deity and is the seventh avatar or incarnation of Vishnu, one of the tree major Hindu gods (trimurti). The Ramayana is the sacred Indian Hindu 5th century BCE verse relating journey of Rama and is one of the largest ancient epics in existence. Much of Indonesia became part of the larger Hindu Majapahit Empire (1293-1527) and, although much of that island empire is now Muslim, Bali remained a Hindu majority. The Ramayana greatly influenced all aspects of Hindu culture, morality, and life, as it is a social and moral code for how Hindus should conduct themselves and live an ethical life. It discusses, among other topics, the duties one has in relationships: how to be an ideal father, servant, brother, husband, or king. It provides the significant teachings of Hindu sages and introduces critical philosophical, ethical and allegorical ideas. The Mahabharata, a second Hindu epic, is the longest poem ever written, contains Hindu history, philosophy, and morality, is about ten times the length of the Iliad and Odyssey combined and an important contribution to world civilization.

The earliest written finds regarding dance masks are an old Javanese language (Kawi) inscription from the 9thcentury, popular legends based on the tales of Prince Panji from the 12th century Kadiri kingdom and later events from the Majapahit Empire (1293-1527). Another written record of topeng dance occurs in the 14th century describing King Hayuk of Majapahit wearing a golden mask and being a skillful mask performer. Current mask dances were probably first developed in Java in the 15th century and they continue to be popular throughout on Java and Bali.

Mask dances appear in many forms, have long been central to Indonesian culture and are vital to stay spiritually connected to their history. They are performed as a way to request ancestors, gods, and spirits to take residence in the physical world of villages, temples, and shrines and pass along their divine energy to aid the living in their daily battle between good and evil. Masks are said to house spiritual energy and were made according to traditional customs and procedures. They are performed to entertain, reinforce cultural standards, and teach the young social and religious practices, history, mythology, and folklore. Traditional mask genres have been and continue to be practiced in Java and Bali and are called wayang topeng in Java. In Bali they are called topeng (literally meaning “pressed against the face”) and a mask is called tapel in Balinese. There are also dance dramas called wayang wong where a limited number of masks are worn in enactments of events from Indian Hindu epics the Ramayana and the Mahabharata as well as the Panji tales. As the Javanese word wayang was originally used for puppet theater (wayang kulit) and also borrowed to also use for dramas, wayang wong is sometimes explained as a “dance of human puppets.” This is also performed in Bali with enactments from Balinese historical chronicles as well as Javanese history.

Balinese Masks

In Bali dances, masks and music performances were always considered sacred and closely connected to the Hindu religion. Their primary purpose was to be an offering to the gods and please them and attract their favor, blessings and protection, and masks and were considered as having great power and great importance. The religious and mystical power of masks is apparent, as, when a carver commissioned to make a traditional mask for a trained dancer (as opposed to a commercial carver) first discovers the tree he can use, he must undergo a purification ceremony, perform certain rituals, and pray for permission to use it for his task. There are also prayers during the mask making process, and the finished piece must be blessed by a Hindu priest, carefully wrapped up, kept safe and be treated as the sacred, religious and important object it is. Likewise, Hindu priests bless dancers using holy water before a performance as the dance is also an offering to the gods, so the quality of their performance as is a key to pleasing them and having their continued blessings.

Topeng Panjegan

Mask dances (topeng) are performed at annual temple anniversary celebrations (odalan) and other holidays on the Balinese religious 270-day calendar, and there are various kinds of traditional mask dance performances. Topeng panjegan is a sacred dance occurring inside inside a temple courtyard inspired by myths and legends about ancient Balinese rulers and heroes. It is a celebration held to please deities and bond with their divine power using a single dancer wearing five different masks and costumes who uses gestures, movements, rhythms, and costumes to express and explain the character of assorted masks, as these are all full faced and preclude speech. One actor representing many characters performs Topeng Pajegan. The dance, masks and costume changes occur within the view of the audience. The masks danced usually include topeng patih manis (sweet mask of a refined minister with a mild temperament), topeng patih keras (strong mask of a martial or authoritative prime minister), topeng dalem (a composed, moral, and graceful king), topeng tua (mask of a dignified old man), topeng jauk (mask of a demon) and the most critical and sacred mask named Sida Karya meaning “can do the work,” which concludes the performance.

Balinese Masks in Our Collection Include:

Topeng Panca

Topeng panca is a less sacred and more entertaining for the audience, deities, and spirits attending and is normally performed outside the temple. Panca is the word for five, as five masks are danced by a group of four or five dancers. There are about thirty accepted masks from Balinese lore and history including the mask of a king, minister, general, clown (penasar), buffoon (bondres), and many more. The story is often narrated by a dancer wearing a jawless half-mask enabling the actor-dancer to speak clearly in kawi (an ancient form of Javanese) or in Balinese to explain the story being performed and comment on its meaning to the audience. There may also be two clowns who argue and provide differing views and comments on the stories performed to amuse the crowd. Routines may alternate between speaking and non-speaking persons, dance and fight sequences and speaking characters providing differing information going back and forth, all with added dramatic musical accents from a gamelan percussion orchestra. Identifiable masks such as Kebo Taruna, the powerful 14th century Balinese minister (Patih) and the Dahyu, a high cast female Brahman, also used for a queen named Raja Putra and for Sita, Rama’s wife in the Hindu epic Ramayana, may appear in topeng panca and also be used in Wayang Wong dramas taken mostly from the Hindu epics the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, but these are dramas and not technically mask dramas as most of the actors do not wear masks.

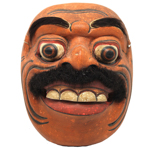

Topeng Bondres

Another kind of mask dance, a more recent independent form, is called topeng bondres. Although many of the masks include clowns, buffoons, villagers, jokesters, servants, and other comical types that have existed in Bali for a very long time, they were initially part of other drama or mask performances and their presence as a independent presentation is rather recent. It is now a separate mask dance variant with lots of half masks allowing speech with slapstick, humorous encounters, and characters voicing zany views and local gossip, and a disregard for conventions provoking riotous laughter from approving crowds. There is always an effort to present opposing aspects of life: beautiful/ugly, cultured/profane, refined/crass, worldly/naïve, unsophisticated-worldly, and this is seen at every performance. The Balinese are lively and fun loving and adore histrionic gestures, teasing, exaggeration, and slapstick comedy. They enjoy making fun of one another and have a very wide open sense of what is hilarious.Bondres masks are not simply clowns, buffoons, and comical types; they include masks with crooked or missing teeth, distorted facial features, giant lips, and other obvious maladies reinforced by irregular movements, inconsistent and overstated gestures, and a disposed Balinese crowd always sees these presentations as uproariously funny and absurdly humorous.

Masks in our collection for the Topeng Bondres include:

Topeng Rangda

Most Balinese villages have a sacred collection of dance masks containing, among other things, the powerful demon-queen Rangda (meaning widow), the personification of evil and head of an army of witches and practitioners of black magic, and Barong her opposite and enemy, the leader of the forces of good, and a lion-like animal with the ability to negate Rangda’s power and the forces of malevolence. He is a good and upright spirit similar to the guardian of the forest in other cultures. The clash between them is not considered a mask dance as the “dance” consists of the only two masks but also has scores of other dance participants featured in an epic encounter called the Barong dance (aka the Calonarang) portraying the timeless battle between good and evil where the Barong restores the traditional balance and stability in the village and its inhabitants.

Rangda masks in our collection include:

Balinese Masks from the Island of Lombok

Lombok, an island about 90 miles east of Bali, is in the archipelago called the Lesser Sunda Islands. Its population is 85% Sasak, the animist farmers who settled there two millennia ago creating a small kingdom before the 17th century. Islam arrived in the form of Muslim traders, as did the Balinese, who ruled the entire island by 1750. However, the Dutch seized the island and merged it into the Netherlands East Indies in 1895. Although Lombok is primarily Muslim, the Hindu-Balinese is now a minority group of about 300,000 who began to build Hindu temples (pura) there in the 17th century, they retain their Hindu culture centered around their temples and continue to be a mainstay of Hindu culture, but are not as traditional as the Balinese, as Hinduism, animism, and Islam are often blend is some ways in Lombok culturally.

Ethnic Balinese and a minority of indigenous Sasak practice Hinduism. All main Hindu religious ceremonies are celebrated at temples in Lombok where many villages have a Hindu majority population. Although mask dances are also performed, extremely few well-carved masks were available for purchase when we were there in the 1970s but the same kinds of mask performances that we have written about Balinese masks were then danced in Lombok. Our collection includes two very different topeng dalem (a mask of a composed and graceful king), two very different topeng tua (a mask of a dignified old man), a topeng jauk putih (a mask of a good demon) and the mini rangda mask above (1265). This collection suggests there was a small market for Balinese masks in Lombok when we were there, no strict standards for making these masks, and very different woods available there from those in Bali.

Balinese Masks from the Island of Lombok in our collection include:

Javanese Masks

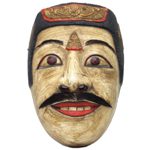

Javanese masks followed an earlier but similar path like those from Bali, as their roots are also in an animistic past and ancestor worship. Unlike Balinese masks, many are often triangular in shape, taper to a narrow chin below a long ridged nose, are brightly painted with polychrome colors and designs following strict traditional styles to create Javanese historical and mythical characters immediately recognizable to most Javanese. Like Bali, historical and ancient epic characters are presented with refined and noble features, while mischievous masks may have bulging eyes and asymmetrical features to express their immoral intentions or bad behavior. Mask dance and drama plots are taken from traditional Javanese epic writings about Panji, the legendary 13th century prince, from histories of the Majapahit Empire (1293-1500), and from ancient the 5th century BC Indian Sanskrit epics the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. These ancient texts are classics, considered sacred, and are presented in a very strict, conservative, and traditional way due to the influence, especially in central Java, of the two orthodox Muslim sultans’ royal courts/palaces (kraton, keraton) of Yogyakarta (Jogjakarta) and Solo (Surakarta). The Javanese accept the characters from this literature as cultural, moral, and historic icons, and performances follow a strict code of conduct and dress code and movements must be idealized to express their importance and significance.

Masked dances were particularly popular and were often held in Javanese courts. Heavily influenced by Islam, they are stylized, didactic and mannered. The courts have long supported mask makers, dancers, gamelan orchestras, musicians, and other performers and have exerted strong influence over the kind of theater and the techniques considered proper for public performances. The dance dramas are rarely affected by modern influences. After the arrival of Indian traders, Hindu epics and Javanese history became the major source along with Indian and local dance to form a unique Javanese style. Mask performances may be held day or night and normally last for hours. Dancers are always ornately costumed and often employed by the sultan’s courts in central Java or supported by government cultural agencies or wealthy patrons to celebrate major festive events. Royal court dances were traditionally free, and, before movies and television, they were major entertainment for rural and local residents. Now, they are rare except those in government supported theaters and tourist centers which now have entry fees.

Like Balinese masks, most topeng are worn with limited exceptions “pressed against the face,” and Javanese dances and dramas employ mostly full-face masks but also have a half-mask jester known in Javanese as a punakawan. The facial shapes and the colors of masks are intended to have different meanings, and character is said to be carved using the same conventions used for wayang kulit, the Javanese puppet theater. (Bodrogi p. 85) Red connotes bravery and strength, white implies holiness or purity, green indicates fertility or everlasting life, while other colors are very difficult to interpret. Dancers undergo similar rituals and blessings to those in Bali, as they were and are still considered the messenger and interpreter of the gods.

Court dances and dramas are extremely formalized to the extent that all movements are very deliberate and self-controlled, and deviations are prohibited, as they are meant to express refinement and composure and used for didactic purposes to teach morality, sophistication, and the proper expression of Javanese court culture. Although there are many gamelan styles in Java and the speed of the music played depends on the dance or drama performed, court gamelan music matches the dance objectives, as it is very traditional, soft, quiet, more suited to palaces, very refined, and extremely unlike the exuberant, energetic, varied, loud, and quick tempo changes of Balinese music. Claire Holt best describes Javanese dance, “Compared to the sudden outbursts of the hyper tense Balinese dancer, the controlled poise of his Javanese counterpart seems an epitome of relentless steadiness.” (Holt, p. 102)

Javanese Masks in our collection include:

Dyak (Dayak) Masks from Kalimantan

Traditional Dyak masks are not limited to those worn on the face. They are seen on shields, doors, walls, and house supports; produced as beadwork designs on baby carriers and other objects, and created in cut cloth and sewn into ceremonial skirts and jackets. Masks are said to act as an obstacle preventing malevolent spirits from entering Dyak spaces and bringing harm to anywhere the mask protects. A mask image safeguards a baby in its carrier, family members in their houses, and the souls of the dead whose bones are kept and honored at a graveyard. Masks of all sizes and subjects are known as hudoq, the same name also used both for the pests able to destroy crops and the Dyak planting celebration. Most ancestor masks have wing-like ears carved separately and tied together using rattan that eventually cracks and must be replaced. Some have wooded tusks or plugs inserted into the lobes, pendulous earrings, attached feathers, or other fastened or painted decoration, and they often have intense round eyes, large bulbous or angular noses, deep set eyes, and mouths with open fanged teeth. Others may be animal caricatures produced to amuse or frighten. Whatever the case, hudoq masks are directly related to the rice cycle festival that entices gods and ancestors to come down from their heavenly home and inspires them to also bring with them sacred rice spirits who ensure crop fertility and drive away all evil spirits who may infect the village or cause harm to the crops.

Indonesian migration and economic transformation after World War II created changes in the social, religious, and artistic practices and culture of Dyak peoples. Although hudoq rice planting and harvesting as well as other religious celebrations have survived for decades, masks were soon influenced by outside cultures, especially those from Java. Masks from the late 1940s or 50s or made since then may have pierced oval rather than half-moon eyes, a straight wide nose with well-defined nostrils, a pointed ridge down the center instead of a curved or bulbous one, attached round instead of separately carved wing-like ears, a small mouth without well-defined or scary teeth which are clear Javanese elements, as well as more modern Javanese patterned decorations. These influences, however, do not detract from the artistry and carving ability of a vintage mask with age made by a very able and talented carver, as those masks usually also validate Dyak hudoq traditions in the overall shape of the mask and using white face paint inside carved outlines. These unique and well-carved pieces would be a welcome addition to any mask collection.

Dyak Masks in our collection include:

“

Timor Masks in our collection Include

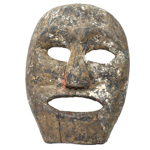

The origin of the mask dance tradition on the Island of Timor remains uncertain, but like all animist cultures around the world the Timorese believe the universe is populated by gods and evil spirits needing offerings for appeasement to protect the living or, in the case of malevolent ones, keep them at bay. Most masks from Timor are carved in East Timor where carvers also made totems and ancestor figures on a small scale, although little is known how they were used. Masks portray both male and female ancestors and were worn only by males at important ceremonies including celebrations of victory in war.

The importance of ancestor carvings is profound, as the communication between the living and the dead was constant and meaningful in animist cultures. Carved figurines from wood and stone required simple tools, and both wood and stone were readily accessible in Timor. Ancestor figures or masks were placed in special areas within the house and also marked the graves of deceased relatives. Offerings of necessities and comforts enjoyed when they were living were made to these relatives – especially food, wine, tobacco and betel nut. When an ancestor was to be consulted for advice or approval, a chicken, goat or buffalo was sacrificed. Ancestor masks were often painted and decorated with the addition animal hide strip and animal hair representing moustaches and eyebrows, and a woven round rattan hat-like head-top ornament. Many but not all masks had eyeholes for the dancer to see; if not they would have to look through the mask’s mouth. Existing masks have holes near the headline, above the eyes, at the sides of the mouth or elsewhere where lost hair, a mustache, or eyebrows were attached. Although many masks were made from perishable materials that did not survive, wood examples have survived as they were preserved and reused for a long period of time. All masks, especially those of ancestors, were considered sacred and powerful and were worn and used to intercede on behalf of the village for its protection from evil intruders and bad spirits. They were also hung above the front entrance and inside the hut for protective purposes and to keep evil of all kinds from entering the house.

Warriors, both male and female, wore masks to hide their identity from enemies. They were seen as being protective along with swords, amulets, shields, ceremonial medallions and headdresses. All were believed to possess the power to protect warriors during battle and were stored in special ceremonial village houses called uma lulik. Special rituals were performed there before the warriors’ departure to “heat” these objects to insure they were effective.

Ancestor masks often have huge deeply cut eyes, a horsehair beard, animal hair eyebrows, a narrow triangular nose, a wide inverted curved U-shaped mouth, and two half-circle ears. They were carved with the intent of portraying a powerful being with the fierce determination to protect its living relatives. Their black color is a result of their extended storage in house rafters above the smoke and soot of the house’s hearth. Home rituals are performed in a large room called “the womb” from which a pillar rises to the roof struts to supports the beams and functions as an axis mundi(the center of the world, world tree, or cosmic axis), the link between heaven and earth and to the gods and ancestral ghosts that watch over the house. The pillar also holds an altar above the floor and is a wooden shelf holding religious artifacts, protective fetishes, and charms that also ward off evil. By the 1980s, “foreign” Indonesian elements were apparent in the shape of the face, teeth, and almond shaped eyes in Timorese masks.

Timor Masks in our collection include:

Sources

I Made Bandem and Frederik Eugene deBoer, Balinese Dance in Transition: Kaja and Kelod, Kuala Lampur, Oxford University Press, 1995.

Jean Paul Barbier, Indonesian Primitive Art from the Collection of the Barbier-Muller Museum, Geneva, Dallas, Dallas Museum of Fine Art, 1984.

Tibor Bodrogi, Art of Indonesia, Budapest, Corvina Press, 1972.

Fred B. Eiseman, Jr., Bali: Sekala & Niskala, Volume I; Essays on Religion, Ritual, and Art, Berkeley, Periplus Editions, 1989.

Fred B. Eiseman, Jr., Bali: Sekala & Niskala, Volume II; Essays on Society, Tradition, and Craft, Berkeley, Periplus Editions, 1990

Claire Holt. Art in Indonesia; Continuities and Change, Ithica, Cornell University Press, 1967.

Judy Slattum, Masks of Bali: Spirits of an Ancient Drama, San Francisco, Chronicle Books, 1992.

Bambang Sumadio, et.al, Art of Indonesia: Pusaka, Singapore, Periplus Editions, 1998.

Online Sources

Encyclopedia.com, “Drama: Balinese Dance and Dance Drama”

Fiona Kerlogue, “Masks from Indonesia in the Náprstek Museum,” Annals of the Náprstek Museum, 38/1, June, 2017.

Second Face, Museum of Cultural Masks, “Asian Masks”

Soedarsono, “Masks in Javanese Dance-Dramas,” The World of Music, Vol. 22, No. 1, 1980.